Santo Tómas, Abiquiu, New Mexico, photograph of the author

Dr. Charles M. Carrillo is an author, santero, and historical archeologist. Dr. Carrillo describes the term genízaro as used by colonial authorities "to describe an ethnic class as well as a social status of detribalized, Hispanicized, Catholic native peoples." Abiquiú has long been identified as a genízaro pueblo. Historical Spanish documents, maps, and more contemporary books describe this group of people in the Abiquiú area.

Map of Northern New MexicoThe 2019 results of a study conducted at Abiquiú Pueblo indicate that the subjects involved in their research carried approximately 40% New World or Native American DNA. According to Miguel A. Torrez and others, the project "offers insight into the historical and contemporary context of the genízaro." The project examined three kinds of DNA, Y, mtDNA, and autosomal. It also completed oral histories, ethnographic studies, and a pedigree chart for each subject. Ten male and ten female community members were the study's focus. These people identified themselves as genízaro or descendants of genízaro, many participants reporting specific tribal heritage.

Tewa people from New Mexico originally migrated to Hopi, living in the First Mesa area after the Pueblo Revolt in 1680. During the 1730s, some Tewa became dissatisfied and returned to New Mexico. This group included some pure Tewa and some mixed Hopi-Tewa people. They moved between ancestral pueblos, including San Juan and Santa Clara, for a few years. Ultimately, the Spanish awarded a land grant in Abiquiú to a small group of twenty-four returnees.

Hopi Tewa, First Mesa, John K. Hillers, photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Settlers constructed modern Abiquiú on the site of an ancient pueblo. Ancestral Puebloans occupied the area from about 1050 until its abandonment in 1200 AD. In 1754, as a way of protecting frontier New Mexico settlements from marauding groups of natives, Mexico established genízaro communities in several areas, including Santa Cruz de la Cañada, Las Trampas, Belen, Abiquiú, and several of the pueblos.

Detail of part of the original wall at Santa Rosa de Lima Church, Abiquiú, photograph of the author

The Spanish established two separate villages in the Abiquiú area. The first was Santa Rosa de Lima de Abiquiú in 1734. The original twenty-four Hopi Tewa may have lived in this village or nearby. By 1754, Governor Tómas Vélez Capauchin, through proclamation, officially established Santo Tómas Apóstol de los Genízaros, the present day genízaro village of Abiquiú. The Spanish then moved thirty-four more genízaro families there, possibly as Dr. Carrillo suggests, to the upper Moqui Plaza area.

House detail, Moki Plaza, Abiquiú, courtesy of Charles M. Carrillo

At least one Spanish slave trader lived in the lower village on the Plaza de Santo Tómas. Others may have lived in the area as well. These villagers, as well as outside slave traders, brought many more native people into Abiquiú over the next 100 years or so. The enslaved native people often mentioned in historical documents included Kiowa, Pawnee, Comanche, Ute, Piutes, Tewa, Pueblo, Navajo, Apache, Laguna, Sandia, and Isleta. The records referred to these native people as genízaro. They were considered the lowest in the Spanish caste system. Spanish documents did not mention Zuni, Tesuque, or Ácoma enslaved people.

Plaza de Santo Tòmas, taken from Moki Plaza, public domain

Modern view of Santo Tómas, photograph of the author

After the New Spain period, census recorders and church officials most often referred to enslaved people as cautivo or captive or, more rarely, Indio. Later, some census records referred to these people as domestics. Some Spanish settlers show in sacramental records as baptismal sponsors of the captives. The settlers held some of them captive while they freed others. Freed Native people often continued to work in their original homes.

Through time, intermarriage blurred the lines of identity and altered many of the traditions. Families expressed their identities in many ways that differed from the original settlers, while vestiges of some old ways remained. Residents and people who trace their backgrounds to Abiquiú and other Hispano communities have, over time, changed the terms they use to describe themselves. Names have included Spanish, Mexican, Mestizo, Chicano, Indo-Hispano, Hispano, Indio, Coyote, and now for many Genízaro. Some community members have stories going back generations describing their family heritage. DNA is now proving deep Native American ancestry as well.

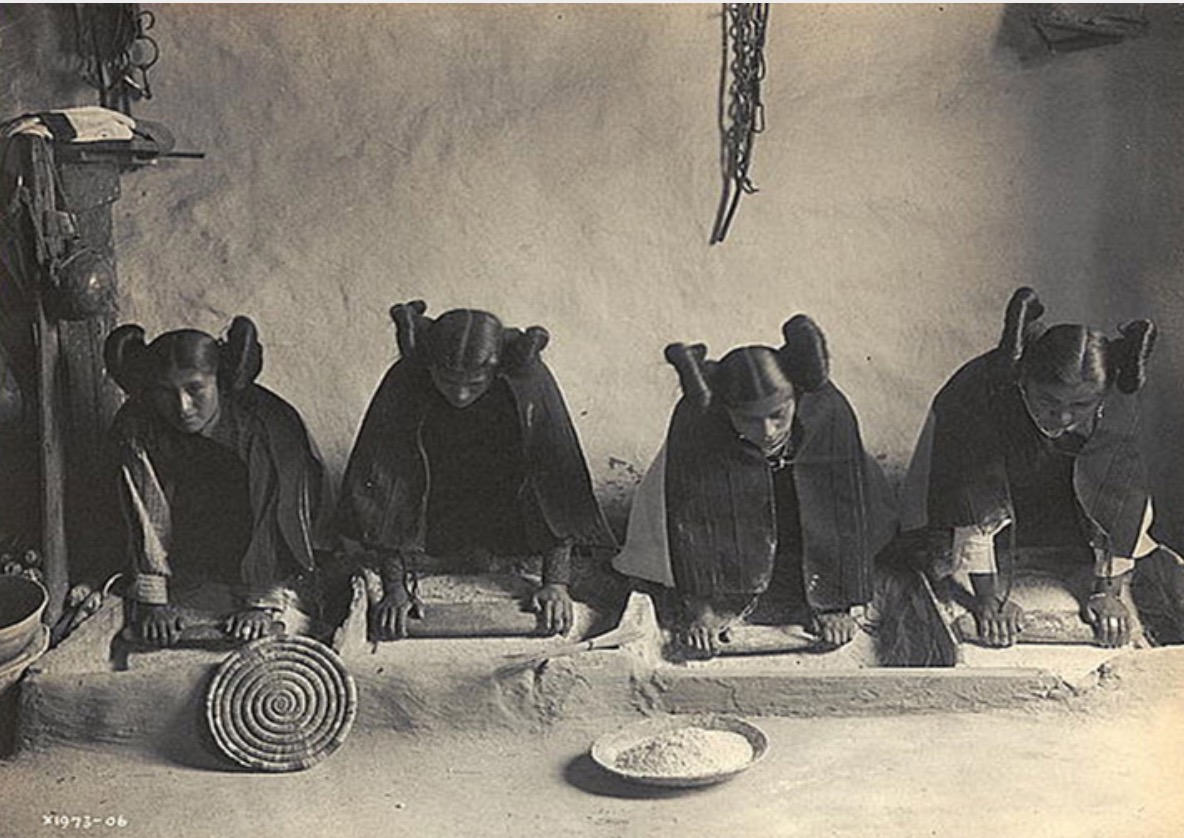

One such family is Debbie's. She did not participate in the study, but some of her family did. Her story follows a similar route to the study's subjects. Her mother's roots have a deep history in Abiquiú. Her grandmother built Debbie's current home many years ago on or near the site of the ancient pueblo abandoned in 1200. Another house where her great-grandmother lived had a small room attached to the back of it. That room contained three metates built into the floor and three manos of varying grit. These were identical in form and setting to those used for grinding corn and other grains in ancient and modern pueblos. Dr. Carrillo identified her 3rd great-grandmother as having been a genízaro. In addition, Dr. Carrillo documented 3 or 4 large cooking stones in village homes resembling traditional ones the Hopis used to cook piki bread. Debbie's family does not currently have any of the stones.

Hopi women grinding corn, Edwards Curtis, public domain.

As in many of the genízaro communities, Abiquiú has dances that resemble those held in Native American communities. Many attribute the dances to their community's mixed heritage. The dances usually take place the last weekend in November for the feast day of Santo Tómas. Debbie's family has a long history of being associated with the dances. Her uncle Floyd was the drummer for many years. His son Dexter is currently the dance leader and drummer. Generations of women in the family have danced, including Debbie's grandmother, mother, Debbie, her daughter, and her granddaughter.

Dances at Abiquiu, courtesy of Charles M. Carrillo

In Abiquiú, one Indita or child's dance is called the dance of Na-ni-ell or Nanillé. This dance is suspected to have Navajo roots. Another dance, called El Cautivo, may point to a genízaro origin. A child from the audience, perhaps the child of a guest or a relative from out of town, is chosen by a dancer. The captor captures a child from the audience, calling, "Who claims this creature?" After being ransomed by the parent or godparent, the captor will call, "Now you are a child of the pueblo." Dr. Carrillo sees this as perhaps ritualizing captivity and redemption. Dancers attend church at Santo Tómas in dance regalia on the feast day of Santo Tómas.

Interior of Santo Tómas, photograph of the author

Dr. Carrillo has traced Debbie's family history through sacramental records.

He has followed one line to an original Hopi Tewa settler of Abiquiú. The baptismal, marriage, and death records of Abiquiú have been located and transcribed. The Genealogical Library of Albuquerque, the University of New Mexico, the Pueblo de Abiquiú Library and Cultural Center, and the State Records and Archives Center in Santa Fe have copies of these transcriptions. Henrietta Martinez Christmas facilitated the donation of an extensive collection of publications, including the sacramental records of Abiquiú, to the Center for Southwest Studies at Fort Lewis College.

Debbie has had her 78-year-old mother's and her autosomal DNA done by Ancestry. Her mother has a DNA estimate of 37% Native American ancestry, and Debbie has 33%. Remembering that her grandmother would say cautiously in Spanish, "Soy India de pueblo," she can now confirm the reality of this statement.

Miguel A. Tórrez, Moises Gonzales, Isabel W. Trujillo, El Pueblo to Abiquiú and its Genízaro Identity, New Mexico Genealogist (March 2019): 8-17.